A chapter from the book: "The Brothers Deiro and Their Accordions."

by Henry Doktorski

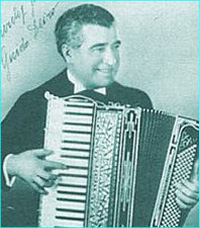

In addition to playing the popular hits of the day and light classical and operatic fare, the two brothers composed their own original compositions. Guido (pictured right) wrote nearly fifty known pieces: fourteen marches, thirteen waltzes, four polkas, four foxtrots, three tangos, three rags, two mazurkas, one quadrille, and one extended semi-classical work, Egypto Fantasia, about half of which were published by Biaggio Quattrociocche of Steubenville, Ohio, beginning in 1916. Deiro had several hits: Deiro Rag was published in an arrangement for piano in 1913, and Kismet, the theme song for a hit Broadway musical which opened in 1911, was published in 1920 in an arrangement by Frank Henri Klickmann for voice and piano.

In addition to playing the popular hits of the day and light classical and operatic fare, the two brothers composed their own original compositions. Guido (pictured right) wrote nearly fifty known pieces: fourteen marches, thirteen waltzes, four polkas, four foxtrots, three tangos, three rags, two mazurkas, one quadrille, and one extended semi-classical work, Egypto Fantasia, about half of which were published by Biaggio Quattrociocche of Steubenville, Ohio, beginning in 1916. Deiro had several hits: Deiro Rag was published in an arrangement for piano in 1913, and Kismet, the theme song for a hit Broadway musical which opened in 1911, was published in 1920 in an arrangement by Frank Henri Klickmann for voice and piano.

Apparently Guido did not write down his own compositions for publication; he simply played his music and his publisher transcribed the notes to music staff paper. Quattrociocche explained, “Guido Deiro had such a wonderful genius for composition. We had arranged that he would play whatever came to his mind, and I would write it down to create new compositions.”

Perhaps Guido did not have sufficient note-writing skill (or time or patience) to transcribe his own music to paper. When I listened to Guido’s records and compared his performances with his published sheet music, I detected many discrepancies which could have been avoided if he had carefully scrutinized the publisher’s proofs. Guido’s genius was not in his formal music training (or lack thereof), but in his gift for crafting beautiful melodies. Galla-Rini explained, “Guido had a very fine touch with his hand on the keyboard, so much so, that a simple melody would sound like a sublime inspiration! Someone said, rightly so, that he had a million dollar touch!”

Guido was not alone in his inability to master the process of transcribing musical notation. Many talented and successful songwriters who were not formally trained in music, such as Irving Berlin and more recently Paul McCartney, had to hire assistants to transcribe their hit songs into standard musical notation.

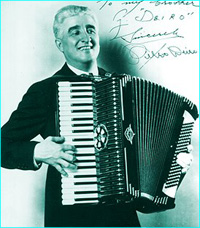

Pietro became an even more prolific composer than Guido, and wrote over 170 original works. Among popular compositions, he wrote at least 37 waltzes, 25 marches, eighteen polkas, fourteen foxtrots, twelve mazurkas, eleven paso dobles, seven characteristic dances, six novelties, six tangos, two rumbas, one rag, and one bolero. Octave Pagani began publishing his music in 1916. Pietro also composed over twenty compositions in light semi-classical style: six overtures, six concert etudes, three sets of variations, two rhapsodies, an intermezzo, a fantasia, a gavotte, a prelude, a rondo, a scherzo, and three lengthy concertos for accordion and orchestra.

Pietro became an even more prolific composer than Guido, and wrote over 170 original works. Among popular compositions, he wrote at least 37 waltzes, 25 marches, eighteen polkas, fourteen foxtrots, twelve mazurkas, eleven paso dobles, seven characteristic dances, six novelties, six tangos, two rumbas, one rag, and one bolero. Octave Pagani began publishing his music in 1916. Pietro also composed over twenty compositions in light semi-classical style: six overtures, six concert etudes, three sets of variations, two rhapsodies, an intermezzo, a fantasia, a gavotte, a prelude, a rondo, a scherzo, and three lengthy concertos for accordion and orchestra.

All of Pietro’s classical pieces were composed in an archaic, albeit popular style: the early Romantic style, epitomized by the oeuvre of Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868), one of Italy’s most beloved opera composers and the composer of the William Tell Overture. Accordionists naturally preferred this type of classical music because unsophisticated audiences found it accessible, and the homophonic textures of works from this era were easily performed on an instrument which was limited to preset bass and chord buttons for the left hand. However in 1949, Pietro broke with this conservative tradition, and attempted something more modern and radical, his Atonal Studies: Compositions in Tonality and the Modern Form.

Despite his reputation as a composer, few people knew that Pietro actually did not compose most of his classical pieces himself; he hired highly-trained and musically-educated ghostwriters to compose his classical scores. This should not be surprising, because Pietro was not a classically-trained composer; he was a successful businessman, a pop musician, and a composer of simple but beautiful melodies for marches, waltzes and polkas. It is unlikely that he could have written a concerto by himself. At least two men worked for Pietro as ghostwriters, Frank Henri Klickmann and Alfred d’AuBerge.

Frank Henri Klickmann (1885-1966), who composed most of Pietro’s classical compositions (and as mentioned earlier, arranged Guido Deiro’s Kismet for voice and piano), was an American composer, arranger and orchestrator of popular music. He wrote in a wide range of genres including sentimental parlor songs such as My Sweetheart Went Down with the Ship (1912 ) – no doubt cashing in on the Titanic disaster, Sing Me The Rosary (1913) and Mama Can’t Pray For Us Now (1914). His ragtime compositions include Knockout Drops: A Trombone Jag (1910), Delerium Tremens Rag: A Trombone Spasm (1913) and Paderewski Rag (1920). Other oddities range from the anti-war Uncle Sam Won’t Go To War (1914) to the fiercely patriotic Old Glory Goes Marching On (1918). He wrote accordion pieces and a concerto for tenor saxophone. Klickmann also worked for Irving Berlin, and wrote arrangements and orchestrations for many of his hit

songs.

Alfred d’AuBerge, a violinist, pianist, composer, arranger, and educator, taught harmony and theory at the Pietro Deiro Conservatory in New York City, and sometimes worked as Pietro’s ghostwriter. Today he is best known for his six volume piano course and guitar method books published by Alfred Music. He also wrote many pieces and arrangements for the accordion, including The Accordionist’s Encyclopedia of Musical Knowledge (O. Pagani & Bro., ca. 1936), and Bellows Shake Made Easy (1957). He also recorded with Pietro for Victor in 1934.

Ralph Stricker (b. 1930), who studied six months during 1949 and 1950 with d’AuBerge at the Pietro Deiro Conservatory, explained, “Pietro Deiro was a great businessman, and did great things to promote the accordion, but he was not a great musician or composer. My theory teacher, Alfred d’AuBerge, told me that he and Klickmann actually had composed most of Pietro’s classical works.”

Anthony Galla-Rini, one of America’s first accordionists to seriously study classical music, supported Stricker’s assessment of Pietro, and claimed that Pietro (and Guido also) were not educated musicians capable of composing sophisticated classical works. Although he acknowledged that they were extremely talented and successful in popular music, he considered them both practically musical illiterates as they “had enough trouble to read treble clef in the right hand.”

Up until then [1938], the left hand [in published accordion music] had been notated with a treble clef. People at that time were very poor readers and bass clef would only make them mixed up. The reason was that Pietro and Guido in their editions wrote the left hand in treble clef and that was absurd. But as a matter of fact, they had enough trouble to read treble clef in the right hand.

Galla-Rini further explained that when the American Accordionists’ Association recommended for logical reasons in 1938 that henceforth all accordion music should be published with the left hand notated in bass clef, Pietro objected because he had a large stock of accordion method books with the left hand notated in treble clef, and he didn’t want to lose any money because of some ideological manifestos about proper musical grammar and notation.

Despite his sometimes myopic vision, it is to Pietro’s credit that he created (through his ghostwriters Klickmann and d’AuBerge) a fairly substantial repertoire of light semi-classical compositions for the instrument. Pietro wanted to “classicize” the accordion (some reviewers compared him to the great classical pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski), and to a certain extent, he succeeded in improving the image of the accordion in America. The accordion world benefited from Pietro’s classical compositions (ghostwritten or not), because these relatively musically-advanced works were performed by accordionists in America and abroad, sometimes even with symphony orchestras, and such performances undoubtedly improved the status and reputation of the instrument.

Yet Pietro did not achieve his success as a composer simply by talent, hard work, and ample money to hire expert ghostwriters. One contemporary claimed that Pietro used his considerable and unscrupulous business “expertise” to “compose” his best-selling waltz: Beautiful Days. Mario Mosti, the son of Joseph Mosti, explained:

My father was good friends with the music publisher Biaggio Quattrociocche, who published about twenty of my father’s pieces. Quattrociocche published a waltz called Beautiful Days (Giorni Belli) by Di Falco. Although it was a popular piece, he unexpectedly removed it from his catalog, and told my father one day that Pietro Deiro had notified him that he (Pietro) was the legal copyright owner of Beautiful Days, and that Quattrociocche would have to stop selling it. Pietro had taken the piece, put his name on it, and registered it with the U.S. copyright office, as if he had written it himself! Quattrociocche couldn’t do anything about it, because neither he nor Di Falco had ever thought to legally copyright the music.

Mosti’s story is collaborated by one 78 RPM record listed in Peter Muir’s discography of the Deiro brothers: Pietro playing Beautiful Days Waltz released by Victor (17551) in April 1914. The composer credited on the label is S. Falco.

© 2005 Henry Doktorski